Karim Abdelaal: From the Soccer Field to the Field of Addiction and Psychedelics Research

Karim is a neurobiology graduate student exploring the therapeutic potential of psychedelics to treat and understand addiction. A former college athlete and self-admitted foodie, Karim also has an appetite for providing inclusive mentorship opportunities.

Trainee Spotlight is a series of interviews from the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences that showcases the science and lives of the people behind the lab coats studying the brain at Duke. Be sure to also explore a list of our spotlighted trainees' favorite spots around town here.

We’d love to hear from you – please suggest someone for the series or nominate yourself by emailing DIBS’s Director of Communications Dan Vahaba.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you study in the Dzirasa lab?

I'm trying to figure out what is going on in the brain that drives drug addiction and how that motivation to seek and consume drugs changes from the first time you take the drug to a state of addiction—from casual use to compulsive abuse. What's going on in the brain and why? Why does it happen to some people and not others?

Part of what I'm doing is trying to look at how psychedelics reshape neural circuits to get rid of psychiatric disorders like addiction. The big hype around psychedelics is that they use a fancy term, "neuroplastigens", which just means they cause plasticity in the brain. From a clinical perspective, psychedelics have had a lot of promise in medical treatments. If I understand the mechanisms that are driving addictive phenotypes, and I can induce a state of addiction, can I then also use psychedelics to not only treat it, but also to understand the mechanism?

What kind of big changes do you hope your research might lead to?

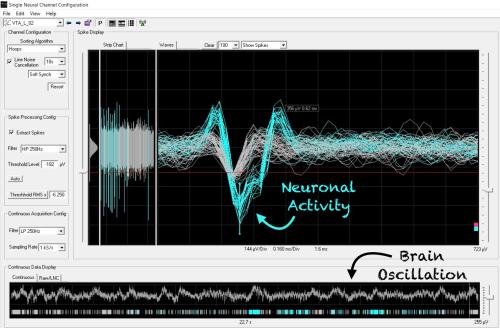

Psychiatry is virtually the only medical specialty that doesn't look at the organ they treat. For neurological disorders, you do MRI scans. For cancers, you take biopsies. In all of these different fields, there is something objective that we can take or image. Psychiatry doesn't have that right now. Being able to find neural determinants, like strongly correlated brain activity, can be used to diagnose people with certain psychiatric disorders. I think that will reshape psychiatry. A lot of the work that's going on in our lab is asking how to develop tools that eventually translate over into humans, which will allow us to predict and create systems in which we can diagnose people based on objective biological measurements for psychiatry.

What kind of big changes do you hope your research might lead to one day?

Psychiatry is virtually the only medical specialty that doesn't look at the organ they treat. For neurological disorders, you do MRI scans. For cancers, you take biopsies. In all of these different fields, there is something objective that we can take or image. Psychiatry doesn't have that right now. Being able to find neural determinants, like strongly correlated brain activity, can be used to diagnose people with certain psychiatric disorders. I think that will reshape psychiatry. A lot of the work that's going on in our lab is asking how to develop tools that eventually translate over into humans, which will allow us to predict and create systems in which we can diagnose people based on objective biological measurements for psychiatry.

What’s one thing you’re especially excited about in your field of research?

One psychedelic drug I'm really interested in is Ibogaine. Iboga is a naturally occurring psychedelic plant that is native to Central Africa, and Ibogaine is the drug that comes from it. It’s a pretty awful psychedelic, actually. People don’t typically enjoy their trips on it, and it lasts anywhere from two to five days. But it has immense therapeutic potential. There are a lot of anecdotal reports of people, specifically with drug addictions, who have struggled with addictions for decades of their lives, and then they trip on Ibogaine once and have remained abstinent since.

How did you find your way to science?

I needed to figure out my life around my junior year in college. I thought I wanted to go into the medical space, but I wasn't really sure. I took this class called regenerative neurobiology, and it caught my attention. A professor who taught the class needed help in his lab, and so I ended up joining and doing physical system processing with mice. It was the first time that I had felt really challenged academically in a way that made me really want to catch up.

What is something people might not know about you?

I have played soccer as far back in my life as I can remember. At one point, I was getting paid to play soccer for a semi-professional team. If I were good enough to have made a career out of it, I would be doing that instead of science. Even though I ended up falling in love with science, my first true love and passion is absolutely soccer. If science doesn’t work out, my backup plan would be to go coach kids’ soccer, which has always meant a lot to me.

Tell us one of your favorite places to grab a bite in Durham.

There is a taco truck that's pretty close to campus called Tacos Chapin right behind the Advanced Auto Parts lot. They are only open in the evenings on some days, but it is one of my favorite places to eat at. A Cabeza Burrito is the best thing to get from there.

What’s one piece advice you’d give to a young researcher?

I mentor a lot of undergrads who come through the lab, and what I tell everybody is to do what you like to do. Prioritize what you like to do. Life will fill up every day from now until the end of time with things that you have to do, and if you allow that to take up all of your time, you won't have any time to do the things that you'd like. It’s a privilege that I get to do science as a job, that I have something that I have to do that I also like. If you are privileged enough to have a career in something that you'd like to do, do that. Don't go with what's going to make you a ton of money or what you have been told to do since you were a kid. Take time to breathe and figure out what matters to you. You can live a life doing things that you enjoy doing, especially if you're good at it.