Matthew Slayton

Trained in classical composition, philosophy, and linguistics, fourth-year Matthew returned to the Bull City for his doctorate in cognitive neuroscience to study how magnetic pulses might help boost memory.

Trainee Spotlight is a series of interviews from the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences that showcases the science and lives of the people behind the lab coats studying the brain at Duke. Want to suggest someone for the series or nominate yourself? Email DIBS's Director of Communications Dan Vahaba. Be sure to also explore a list of our spotlighted trainees' favorite spots around town here.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What got you interested in science?

I think I always liked science, typical things like dinosaurs and space and volcanoes when I was younger. But I've been in a couple of different academic disciplines at this point, so I kind of fell into what I'm doing now.

I studied neurolinguistics in undergrad at Duke, and I’ve been in a couple of grad programs. I was in a philosophy Ph.D. program and mastered out with a degree in philosophy of biology. I worked for a couple of years in a cell biology lab studying leukemia. And then, I started getting into neuroscience when I was in music school. I did a master's in music composition and a neuroscience independent study with someone there. I sort of realized that cognitive science is right in the middle of linguistics, cell and molecular biology, and music.

What do you study at Duke?

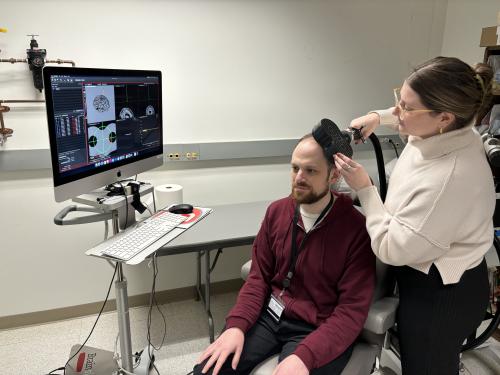

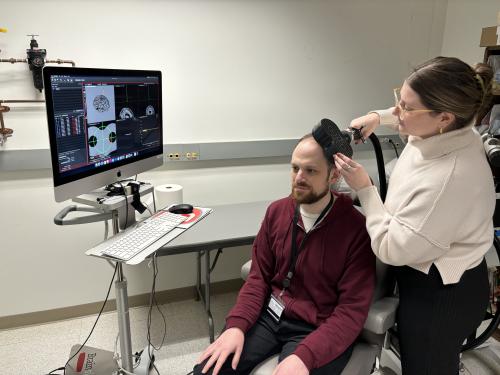

I am a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate, and my dissertation is about investigating the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Our hypothesis is that TMS can enhance the representation of semantic information during encoding which in turn improves memory recall. There might be structural changes to white matter tracts as well. Stay tuned because the work is ongoing!

It has been investigated in memory disorders for the past decade or so. It's all non-invasive—a coil that you put right at someone's scalp and it delivers a magnetic pulse. Something like electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or deep brain stimulation (DBS) can have a much bigger effect, but TMS has practical advantages. It's much easier to use and the infrastructure already exists. This is a trade-off that doesn't require surgery.

TMS is used in the clinic right now for a number of psychiatric disorders, primarily depression, OCD, and PTSD. But there's also interest in using it in neurology. It appears to have a small but noticeable benefit to memory, so we're trying to understand the how and why of that effect. We would like for it to be used in the clinic sometime in the future!

I am excited about the potential for TMS. I've gotten the opportunity to shadow in a few different clinics this year. I'm in the Duke Scholars in Molecular Medicine (DSMM), so I was able to shadow at Duke Neurology and see the Memory Disorders Clinic’s outpatient management of Alzheimer's. TMS may not be the moonshot of Alzheimer's, but you don't need a moonshot necessarily. You just need options. I'm excited about the potential for treatment options to add to what’s available.

What do you love most about your research?

I really like the participants. We work with a patient population—older adults who have mild cognitive impairment, which is a memory disorder. Working with them is the best part, what I most consistently enjoy. The people who volunteer for a study tend to be really open, generous people, obviously with their time. I’m really motivated by translational research and getting to work with a patient population in a research capacity.

What else are you involved in at Duke?

In addition to the DSMM, I'm in the University Scholars Program. It has undergrads, as well as graduate and professional school students. Every year, there's a symposium where students give presentations. It also involves mentorship. I’ve been paired with an undergrad, and I meet a couple times a year.

I have also been lucky to receive travel awards for research, including the Karen L. Wrenn Alzheimer’s Disease Travel Award. Supported by that, I will have the opportunity to present results at places like the Alzheimer's Association International Conference.

With such a varied academic background, what made you choose to stay in cognitive neuroscience?

If you do a composition Ph.D., you typically have some kind of academic component. I said, I'm going to do a science project, and the more I did science, the more I got into it. And then, when it aligned that there could be a translational focus for me, I started to get really excited about neuroscience.

As somebody who previously studied music and still composes it, what does music mean to you?

It’s an academic interest, hobby, passion—kind of all of the above. I've been composing for a long time. I've had some limited success at composition. I studied music here at Duke as an undergrad, and I thought it would be a side thing, but I realized that I really wanted to fill out the gaps in my training. I could call it a hobby because I’m not doing it primarily, but a lot of classical composers have a day job. If my day job can be anything, why not have it be science?

My current goal is to make something that you could play on Spotify while you're working. When you're writing ‘serious’ music, you need everyone to be quiet and listen. That's not how most people listen to music most of the time, with completely rapt attention. So, I'm collaborating with a game designer. I've made the music and am waiting on the game release. Fingers crossed it will be out soon!

Where do you call home?

I grew up in New Jersey. People used to call Duke University of New Jersey at Durham, but no one now recognizes that. Is that not a thing anymore? It’s making a joke about all the New York area transplants at Duke and the Triangle.

Having lived in Durham both through undergrad and now, do you have any favorite spots?

There’s this place on Ninth Street, Banh’s Cuisine. They have specials on certain days of the week, and there’s this vegetarian platter. I don't know what they do with that tofu, but it's so good. That's my niche Duke food recommendation.

Do you have any hobbies outside of all that you do?

Well, I don't really hike. I think every academic has a photo of them on a mountain. I actually like neighborhood walking—city walking—more than the vertical climbs.

What is a pro tip you’ve learned over your years in academia?

For grad school, I’m thinking about advice I’d tell my younger self. I’d say to work on a project even if it’s not your favorite topic. Students can be overly focused on finding a research project that is a perfect fit for their interests and goals. There are many practical hurdles and challenges to doing science that require experience to deal with, and you can get that experience on any project, regardless of what the topic is. So, my advice is to jump in to any research assistant position because it will still be valuable preparation for future projects that are closer to your interest.

If you are a Duke undergraduate, graduate, or postdoc student studying the brain and would be interested in taking part in an interview for this series or would like to nominate somebody, please reach out to Dan Vahaba, Director of Communications at DIBS.