S. Monroe

As a third-year neurobiology graduate student in the Bilbo Lab, S. Monroe has spent their time at Duke pursuing the intersection of their three main interests: research, art, and science communication.

Trainee Spotlight is a new series of interviews from the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences that showcases the science and lives of the people behind the lab coats studying the brain at Duke. Want to suggest someone for the series or nominate yourself? Email the DIBS Director of Communications Dan Vahaba.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I. Kjaerulff: Tell me a bit about your research.

S. Monroe: I'm really interested in how our brain interacts with the rest of our organs. The Bilbo Lab broadly looks at microglia, which are immune cells in the brain, so I'm very interested in how the brain responds to immune inflammation in the periphery. I'm looking at, in the context of a lung infection with influenza: How does the brain learn about this infection and respond to it?

IK: What do you think is a broad impact of the research that you're doing?

SM: I think the most immediate impact is understanding how immune challenges to the lung impact our overall health, particularly our cognitive health. Immune challenges to the lung can include things like air pollution, COVID and other novel respiratory viruses, asthma, and allergies, which are increasingly prevalent in urban society. Because our brain actually responds to immune challenges in the periphery, and our brain is a very delicate organ, we need to understand how it's going to impact the cognitive health of our population going forward.

IK: Absolutely. So then, what do you love about science, about your research, or just what you do?

SM: My favorite part about doing the science is playing with the test tubes. I like to physically enact experiments. All of the tools that we use are so powerful, and we have access to a lot of things in the lab and at Duke.

But my other favorite thing about science is actually talking to people about it and telling people about it—teaching people. Neither of my parents is a scientist, and they have different levels of understanding of science. My dad is familiar with the basics of CRISPR and that level of science education, so I can go into detail about some of the tools I use. For my mom, she has less exposure to science, so I share the big-picture questions of my work. Trying to figure out how can I communicate these complicated concepts to a general audience at different levels is really fun for me.

IK: How did you get into research?

SM: I got into research when I started college. Growing up, I was always really passionate about art. I didn’t want to become an artist, though, because I think that there are a lot of challenges with creating a profession out of it. So instead, I decided to pursue science, which was also very interesting to me. I think that I was drawn to the potential of science and also the stability of science as a career. When I was an undergrad, I got a work-study position and worked in a caterpillar and butterfly lab. I did an undergrad project—also in a butterfly lab—using CRISPR, and then I switched over to neuroscience.

I did a joint degree, so I was a full student at both UNC Chapel Hill and the National University of Singapore. In Singapore, I used CRISPR to knock out a gene for the eyespots of butterflies. We disrupted their formation and coloration to characterize the gene pathway for these eyespots. It's actually the same gene pathway that makes legs and antennas, so you can imagine how a leg became an antenna in evolution. But it's a lot harder to imagine how it became an eyespot. How do the genes that normally make appendages make a flat disc? So, we were studying, How did that gene pathway get transferred over to butterfly wings? Why does it work so differently there?

IK: What do you want to do after your time at Duke? Big dreams are totally welcome.

SM: My biggest dream would be in visual science communications doing art for other scientists and working for an institution to help promote their art or science to the public, so some kind of communications role, whether it's for a journal or an institution.

Another realm I'm interested in is science policy, which would be more like analyzing scientific literature and writing reports to help inform institutions—likely the government—to make different legislation or policy decisions.

IK: Let’s say you can only use a couple of items in your lab or work environment for the rest of your career. What are you taking?

SM: That’s a hard question. Our microscope is really cool. Being able to collect visual data from your tissue creates powerful possibilities. We look at a lot of cells and cell morphology. Microglia are immune cells, and their shape changes a lot depending on what they're doing in the brain. They can have a very ramified, branching shape. But they can also have a rounder, amoeboid shape depending on what kind of actions they're taking in the brain. The kind of visual information we can get by looking at cells is really important to what we do in the lab, so that's definitely one tool.

And then, I think another interesting tool I use in my work is qPCR, which lets us take a really easy and quick snapshot of what's going on at the transcriptional level, which genes are being used and expressed right then and there in the cells.

IK: Do you have anything you want to share about your most recent research?

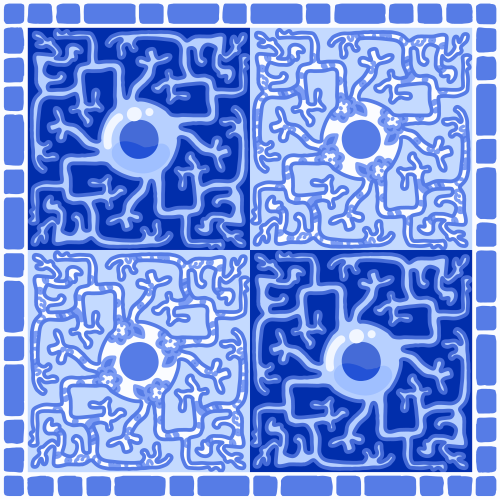

S. Monroe: The brain has many cells other than neurons, including glia. Some of these cells will be very highly branched and reach around to touch and sense many things in their surroundings. They create discreet territories that they're in charge of surveying, and then the neighboring cells will have their own non-overlapping territory. This cellular phenomenon is called tiling, which inspired the direction of this piece.

SM: We know that during a lung infection, microglia create their own immune response, even if the infection is only in the lung and not in the brain. So, we typically think the lung becomes inflamed, and it releases inflammatory molecules that circulate through the blood, and then the microglia can detect that. I'm also looking at a faster route because that information takes days to set in, and I actually saw that the brain responds more quickly—specifically, the neurons change their activity. And so, I think that maybe the vagus nerve is a faster signaling route. That's something I'm exploring in my research.

I'm also looking at the development of the brain and lungs, specifically if there are long-lasting behavioral changes to the offspring if their mom is stressed right before they’re born. I'm also looking at if there are long-term changes to brain communication, either through the vagus nerve or through other inflammatory mechanisms.

This is all preliminary data. Since I'm in my third year, a lot of my work now is trying to feel out, OK, how can I make these new tools work in the lab? How can I see interesting results? And what do I want to pursue further, laying the foundation for future experiments? I have this idea that the vagus nerve might be communicating the things I'm interested in, but I'm not totally sure yet. I'm trying to find some preliminary information that supports that before I spend two years pursuing those experiments more deeply.

IK: We were talking about your identity as a science communicator, and you have a few blog posts that I've come across. Could you tell me a bit more about that?

SM: Communications is in many realms of my life. Art has always been my biggest hobby, so I like to pull it into my professional life and my advocacy. Right now, I'm the president of Duke's chapter of oSTEM [Out in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics]. It's a queer professional organization, and it has many chapters across the country and in other countries. It’s a space where we can create community and advocate for better representation and rights for groups of people within STEM fields. I do a lot of communications work for them as well.

I've also done a lot of figure-making for other labs. I've collaborated with labs where I don't even touch their research, so I had to try and understand it and create a clear visual figure that is accurate to the science. I've also done logos for labs and animations for public outreach. Just doing a lot of art in connection with other organizations is something I'm passionate about.

IK: Are there any pro tips you've learned from that?

SM: Canva is, in my opinion, the easiest and most accessible resource for people to make visual media that don't normally make visual media. It's super powerful, really good for any kind of flyer.

IK: Absolutely. So, I've seen your art in Cell Press. I know you've kind of talked about the role that visual arts play. Where did that start?

SM: Just as long as I can remember. I’ve been drawing since I was a baby. I also did a lot of crafts when I was young. I'd make clay, wire, and bead sculptures. I pursued many mediums of arts, but it was always I felt that being an artist as a profession is not something I want because I like more structure to my employment. It's something I never really considered as a profession, but it's something I always hoped to tie into my profession. I'm trying to find the sweet spot of, Can I be a communications professional without doing freelance work? I’m seeing more opportunities pop up across the science industry and academia every year.

If you are a Duke undergraduate, graduate, or postdoc student studying the brain and would be interested in taking part in an interview for this series or want to nominate someone, please reach out to Dan, the Director of Communications at DIBS.